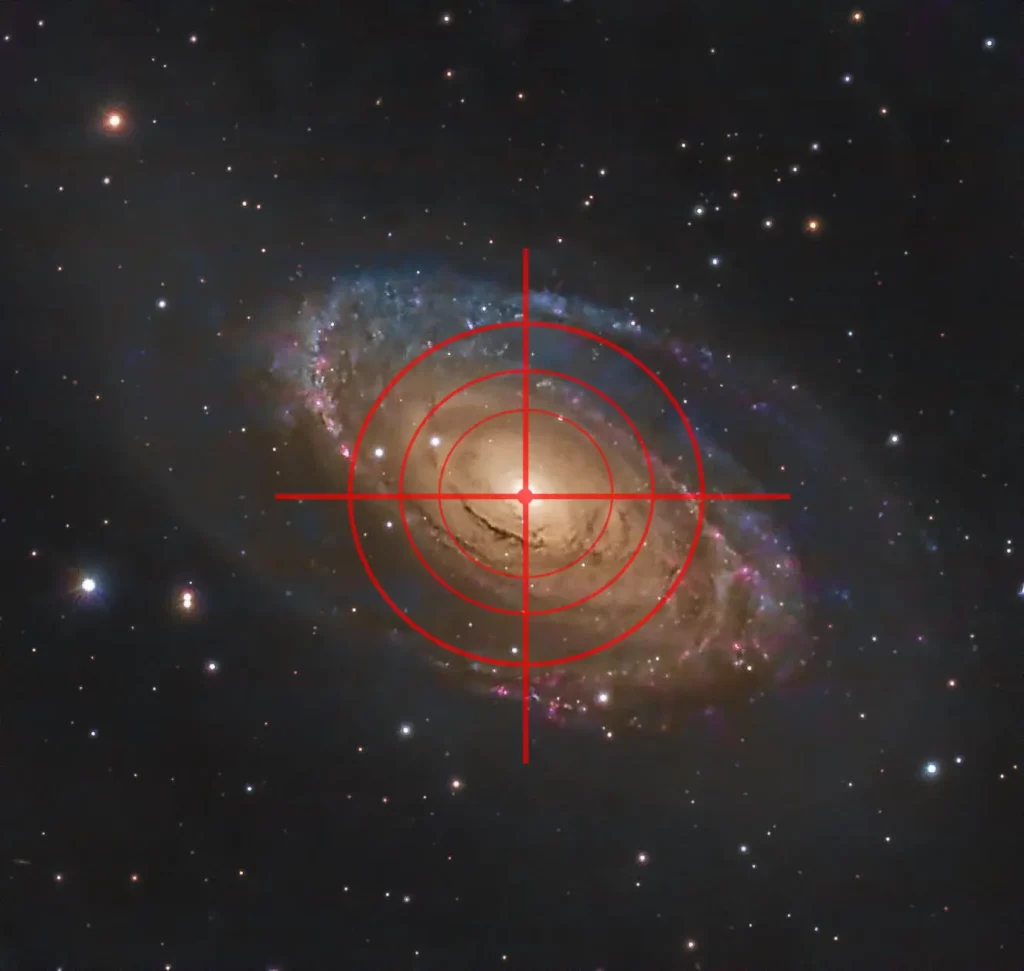

It ain’t duck season and it ain’t wabbit season!! It’s Galaxy Season!!!

I’m an astrophotographer, and I hunt galaxies!!

When is galaxy season?

Galaxy season occurs during the spring in the northern and southern hemispheres respectively. It is when the Earth’s position and orbit around the sun offer optimal conditions to see distant galaxies in the night sky. Earth’s orbit causes the Milky Way to appear higher in the sky making it easier to see galaxies and other objects.

While you can still image certain galaxies (i.e., M81, M82, M31, M51) outside of this time of year, springtime provides the best opportunity to observe the fainter, more distant galaxies, and galaxy groups only visible during this period. What I enjoy about viewing galaxies are the different shapes. When asking a person to draw their idea of a galaxy, most may give pictures of large spiral arms with a central bright core. Most are, in fact, spiral, but galaxies can come in different shapes and classifications. Some may have arms, some won’t, some are irregular or lenticular shapes, and some spirals we can only see from the side, like Messier 104, The Sombrero Galaxy. Then, there are the galaxy groups like the Triplet or Hickson 44 in Leo, or Markarian’s Chain which is part of an even larger galaxy cluster pulled together by gravity in Virgo. There is a lot to see when the Milky Way curtain is drawn back to show more of our area of the cosmos.

What equipment is best suited for imaging galaxies?

When capturing images of far-off galaxies, it’s strongly advised to use optics with a high capacity for gathering light and a long focal length. Telescopes I would consider the minimum for these targets are at least 4 ½ inch aperture and 900mm focal length. Apochromatic refractor telescopes such as my former William Optics Zenithstar 126 (927mm), or the Explore Scientific ED 127 are good choices. These types are good all-around telescopes because, at their native focal lengths, you can capture targets in Leo such as Messier 94 (The Croc’s Eye Galaxy) or the Whale (NGC 4631) and Hockey Stick (NGC 4657) galaxies in Canes Venatici, or when using a 0.8x reducer can capture emission nebulae such as the Wizard Nebula (NGC 7380) or the Western Veil (NGC 6960) and Pickering’s Triangle (NGC 6979) supernova remnants with an APS-C sensor.

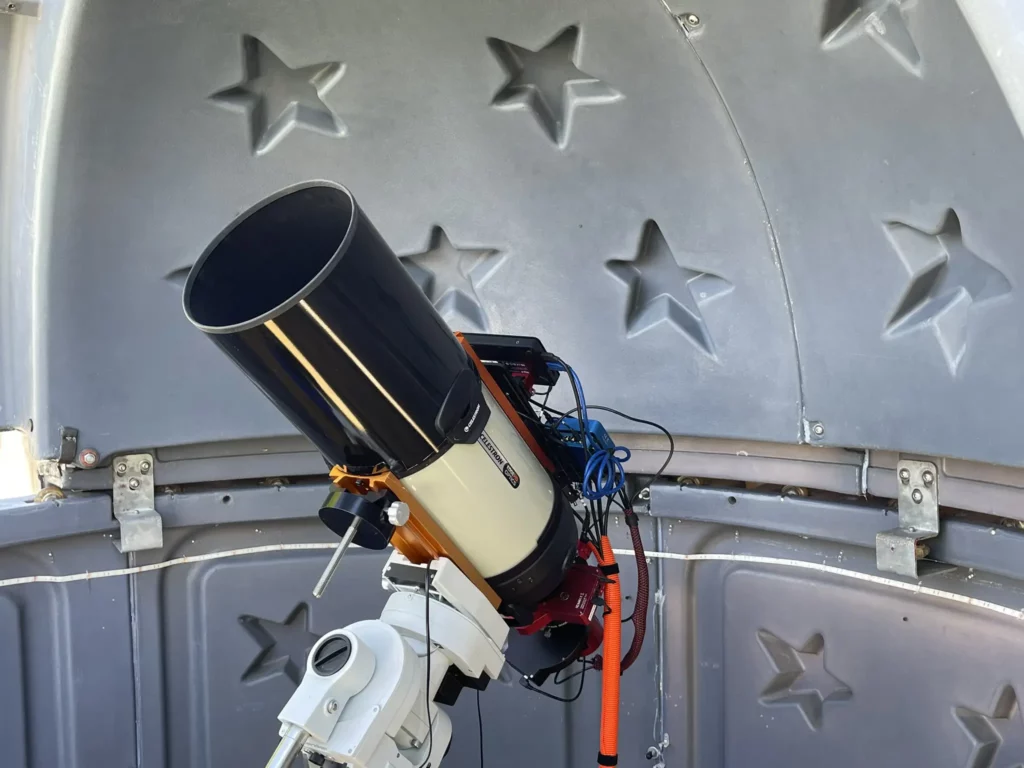

But if you want to go further, consider reflector/mirror-based telescopes like the Schmidt-Cassegrain (SC) or Ritchey-Creitchen (RC). These offer much wider apertures, I’d go no smaller than 8-inch, and long focal lengths closer to 1500mm and greater. I use the Celestron EdgeHD 8 for photographing galaxies, it has a focal ratio of f/10 and a focal length of 2032mm or if using the 0.7x reducer it has a faster f/7 focal ratio and 1421mm focal length. A similar-sized RC is f/8 and 1600mm focal length. Regarding faint targets like galaxies, the larger the aperture the better for pulling in more light.

I gotta bring up collimation

I’d be remiss if I did not bring up this topic, especially regarding reflector telescopes. Unlike refractor telescopes that use glass elements and so, not required, one item of note with reflector-based telescopes must be considered, collimation.

Performing regular maintenance is key to getting the best out of your equipment. For mirrored systems, such as SC, RC, and Newtonians, you will need to check the alignment of your mirrors and realign or collimate them. If you do not, the stars will be skewed, and your images will not look good. Collimation is a necessary evil with these systems and will need to be learned early on as an owner of one of these telescope types.

Personally, my only issue with Ritchies is their collimation process. It’s longer and requires alignment of the secondary and primary mirrors, plus the focuser. It is more involved and requires additional tools, but as I have seen from RC owners’ Astrobin photography pages, once you are accustomed to the process, it doesn’t take a very long time and can achieve outstanding results.

In contrast, Schmidt-Cassegrain collimation is easier as it only requires small adjustments of the 3 screws on the secondary mirror to align it with the rear primary mirror. There are tools such as tri-bahtinov focusing masks, or camera collimators that can help in this task, but for the most part just pointing to a bright, unfocused star to see the outline of the secondary mirror is all most astronomers need to accomplish this. I would recommend caution with using a metal screwdriver anywhere near the corrector plate. I’d suggest looking into nylon screwdrivers, or I have personally replaced my stock collimation screws with properly sized stainless steel socket head cap screws. If you do decide to replace your collimation screws in your Schmidt-Cassegrain, contact or check your manufacturer’s website to ensure you purchase the correct-sized screws. Here is the link to Celestron’s page with this information,

https://www.celestron.com/blogs/knowledgebase/what-are-the-sizes-of-collimation-screws-on-current-production-celestron-optical-tubes.

I cannot speak to the collimation of Newtonians, as I have never owned one. But I know of a collimation camera tool called the OCAL that can be used to collimate Newtonians, I own one as they can also be used to collimate SCs and I think, RCs too. The nice thing about this collimator is that it can be done indoors, which is very nice, especially during the winter months.

Final Thoughts

There is a season for everything when it comes to astronomy and astrophotography. Springtime is galaxy season, until the Earth’s orbit shifts back to facing the Milky Way there are very few nebulae to image. So don’t miss out, astrophotographers make the most of this time possible by changing from widefield to narrow, long focal length optics. As an astrophotographer mindful of expenses, I’d like to point out that while collimation may not be everyone’s favorite task, mirrored telescopes offer a lighter, more affordable option with the capability to observe and photograph distant galaxies. Refractors with comparable specifications necessitate larger, heavier glass components, rendering them cost-prohibitive and challenging to utilize in backyard observation setups.

What are your thoughts on galaxy season? Are there any specific galactic targets you have in mind or currently observing with your telescope? Feel free to join the conversation, share your comments, and connect with me and fellow astrophotographers.